“If you break your principles in the little things, each time it becomes easier for the bigger things.”

The sentiments in this line, uttered by a friend of my grandmother’s family, have guided many principled men to greatness. And yet they have doomed many more.

Tyrannical regimes rule by whim and diktat, and, for that reason, are the opposite of principled—and so, they do their best to remove and destroy the principled men who stand in between them and doing whatever they wish.

So it is with many today, and so it was with a friend of my grandmother’s family, Professor Svoboda.*

Professor Svoboda was a professor of art at the Charles University in Prague, the largest and best university in the Czech Republic and one of the oldest continuously operating universities in the world. He lived in Prague with his six children and, as my grandmother described him, was known for being a principled man.

It was his principles that got him in trouble with communist authorities.

In Soviet countries, one of the biggest celebrations of the year was May Day, which occurs on May 1 year. The leaders give speeches, the public wave flags, the military performs marches, and the people celebrate the wonders of communism and its workers.

The people of Prague were instructed to fly two flags—the Czech flag and the Soviet hammer and sickle. Professor Svoboda only had the Czech flag, and so he only flew the Czech flag.

This was seen as an insult by the communist authorities, so Professor Svoboda was reprimanded and instructed to find a red flag in the next two hours.

He did not submit to the bullying.

His refusal to submit started weeks of harassment, name-calling, and public critique. He was called a fascist and an enemy of the people.

All he had to do was recant and fly a red flag.

He did not, because, “If you break your principles in the little things, each time it becomes easier for the bigger things.”

After weeks of harassment, he was fired from his job at the university and couldn’t find another. No one wanted to hire an enemy of the people.

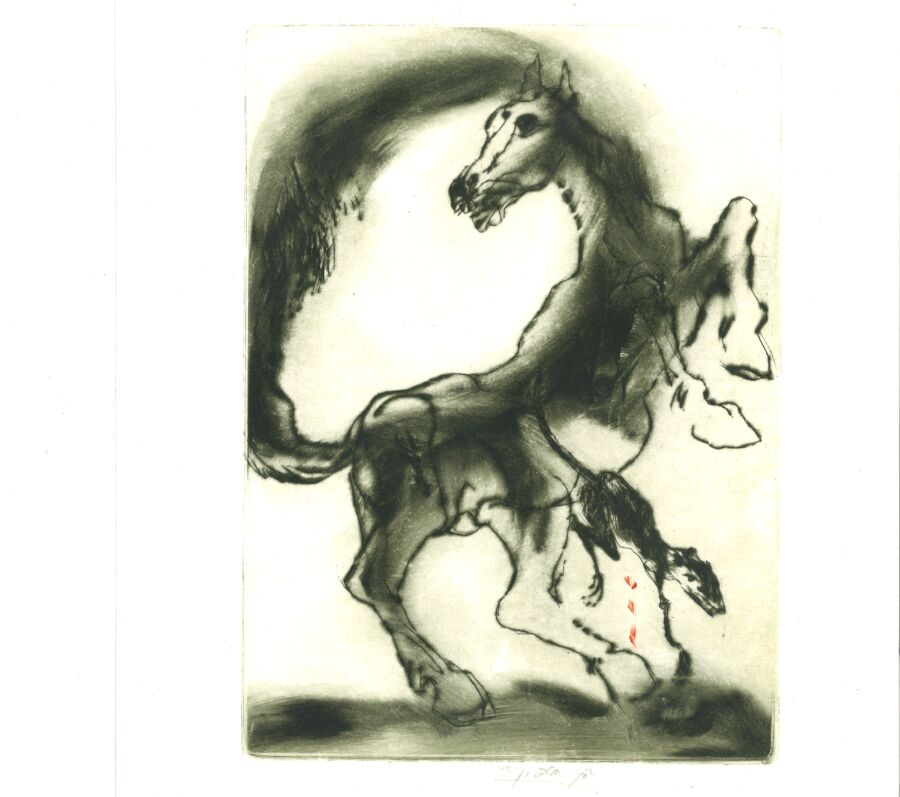

Eventually, the city hired him as a street sweeper and paid him just enough to barely feed his family. Throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, my grandmother’s family mailed back and forth with Professor Svoboda and provided small necessities and luxuries like shoes, coats, sweaters, chewing gum, and chocolate. The professor responded by sending hand-painted watercolors made on the scraps and bits of good quality paper he could find.

My family all admire his and his family’s courage, and one such painting occupies a prominent place in my home.

In Texas and some other states across America, Nov. 7 is observed as Victims of Communism Day. This Victims of Communism Day—and almost every day, as I walk past my painting—I think of the brave men and women like Professor Svoboda who, even if their actions may not have been dramatic or revolutionary, in their own way stood up against communist regimes and paid the price.

And, in honoring that memory, I resolve not to let such things happen here.

*Svoboda is a pseudonym for the professor out of respect for his family’s privacy. Svoboda can be translated as “freedom.”