Two weeks ago I warned that Mexico was dangerously unprepared for a coronavirus outbreak and that once it hit, it would spread quickly, overwhelming a weak and corrupt Mexican state and a woefully inadequate health-care system. Despite warnings from health officials that an outbreak was inevitable, the Mexican government had done almost nothing to prepare and refused to take the threat seriously.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador repeatedly dismissed the need for caution, urging Mexicans to go shopping and eat out. He even took his own advice, staging large campaign-style rallies, kissing babies, embracing supporters, and saying things like, “You have to hug, nothing is going to happen.”

Well, now something is happening. On Monday, Mexico declared a state of emergency as the number of confirmed cases exceeded 1,000, with at least 28 deaths and counting. The number of actual cases is no doubt far higher (by Tuesday, the total was more than 1,200) but because Mexico has not scaled up testing like other countries have, and appears to have little capacity to do so, we don’t really know the extent of the outbreak. Experts estimate only about 10,000 people have been tested so far nationwide—one of the lowest testing rates in the world.

Mexico ordered schools and most government offices closed last week, and on Tuesday expanded the shutdown to all “non-essential” activities and businesses, while prohibiting gatherings of more than 100 people. But the order, which will stay in effect until the end of April, appears to be largely voluntary, with no enforcement mechanisms or penalties. It is almost certainly too little, too late.

Government officials have been pleading with the public to stay indoors, with mixed results. In Mexico City, a metropolis of some 20 million people, the shutdown is being observed inconsistently. Wealthier neighborhoods, whose residents can afford to stay home, have gone mostly quiet in recent days, while poorer neighborhoods and markets largely have carried on with business as usual.

The Central de Abasto, Mexico City’s main wholesale food market, has remained busy and crowded this week. Some merchants have even taken to posting on social media that the coronavirus doesn’t exist, that it’s a “trick of the government with other countries to get into debt.”

You can hardly blame them for thinking so. For weeks now President López Obrador has more or less done the same, denying the threat of the virus and at one point telling a crowd that the disease is “not going to do anything to us.”

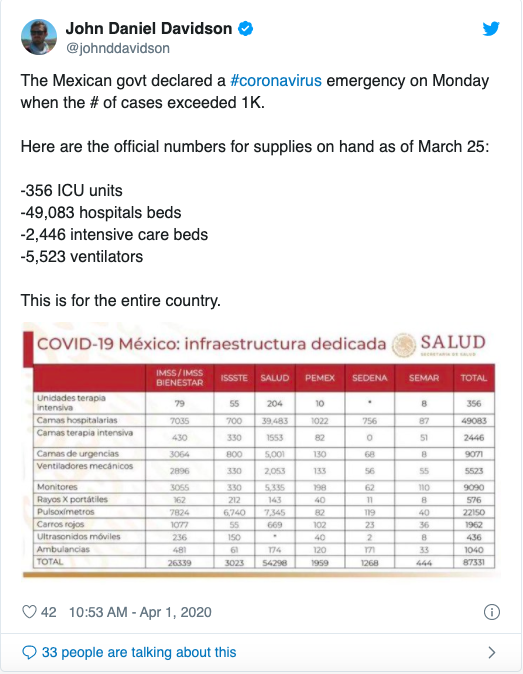

Yet the raw numbers of supplies on hand suggest an impending humanitarian catastrophe. Mexico, with a population of 130 million, has only 356 ICU units, fewer than 50,000 hospital beds, fewer than 2,500 ICU beds, and just 5,523 ventilators. That’s for the entire country. (For context, New York City alone has about 6,000 ventilators and more than 2,000 ICU beds.)

“We won’t have supplies in time, ventilators, protective equipment for doctors,” says Xavier Tello, a health care policy analyst in Mexico City. “But if you ask the government, they are defending their timing. They claim they were planning this three months ago.”

The main reason for this drastic supply shortage is deliberate government inaction. Early on in the crisis, officials refused to manufacture test kits or authorize their purchase. Same for N95 masks and other protective gear. The government only began expediting orders of these supplies from abroad late last week.

Meanwhile, López Obrador continues to invite scorn for his cavalier approach to the crisis. Over the weekend, he ignored the public exhortations of his own health officials—that people stay home—by traveling to the hometown of the infamous drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán and shaking hands with the kingpin’s mother. On Monday, he claimed that if he self-quarantines his political rivals will take over. “Do you know what the conservatives want? For me to isolate myself,” he said.

What This Means For The Border

Mexico’s unpreparedness, combined with woefully incomplete data about the extent of confirmed cases across the country, present real dangers to the United States, especially to communities along the southwest border.

Although the Trump administration imposed a partial closure of the border on March 17, shutting down all “nonessential” travel, the nearly 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border is inherently porous, with a constant flow of licit and illicit goods going back and forth over the Rio Grande every day.

It’s true that travel restrictions have quieted once-bustling border crossings in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, and the streets of Laredo, Texas, where on average 10,000 people cross the pedestrian bridge daily to shop and attend school, are deserted. But cross-border traffic continues apace, from commercial truck drivers and farm workers on agricultural visas to powerful drug cartels trafficking narcotics. (Last week in Laredo, Texas, U.S. border officials seized a single shipment of meth worth $37 million.)

In addition, the illegal flow of migrants across the border hasn’t stopped altogether because of the pandemic. Last month, more than 30,000 people were apprehended by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, including 3,600 single adults. The number of illegal border-crossings has, however, fallen to near-record lows over the past year in part because of Trump administration policies designed to deter asylum-seekers.

Since the administration put in place emergency measures on March 21, the number of daily illegal crossing has plunged even further, to fewer than 1,000. Most of those now caught crossing illegally are sent back to Mexico in an average of 96 minutes, a dramatic change from previous policy and much closer to the rapid deportation approach to border security that Trump has long advocated.

However, even under the terms of the emergency agreement, Mexico has refused to accept migrants from countries other than Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Citizens of all other countries who are caught crossing the border illegally are being taken into CBP custody as before, as are migrants with arrest warrants or serious criminal records.

Cross-border air travel also continues apace. Mexico is the top destination for American tourists, and as of this writing commercial flights to and from the United States and Mexico were still running. The dangers of air travel were underscored this week with news that 28 University of Texas students who traveled to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, for spring break have tested positive for coronavirus. They were with a group of 70 spring-breakers who flew to Mexico from Austin, Texas, about a week-and-a-half ago.

The incident also underscores the unreliability of official data on the virus from Mexican authorities. As of Monday, the total number of confirmed cases in all of Baja, California (Cabo is located on the southern tip of the Baja peninsula) was only 31—about the same as the total number of UT students infected over spring break.

According to Tello, the health care policy analyst, many health professionals in Mexico are questioning the coronavirus numbers at the border on account of the massive differences between confirmed cases in Mexico and the United States. San Diego County has 734 confirmed cases compared to Baja California’s 31. As of Sunday, Arizona had 919 cases, while neighboring Sonora state had only 14. New Mexico had 237 cases, Chihuahua state had only six. In the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, there are a total of 121 cases in the five counties that border the state of Tamaulipas, which has just 8 confirmed cases.

All of this suggests the virus is already widespread in Mexican border communities, whose health care systems are ill-equipped to handle even a small outbreak. Based on what we know now, it looks like Mexico is about to get hit with much more than that.

When it does, U.S. officials will need to be ready to take unilateral action to secure the border. Mexico’s endemically corrupt and incompetent officialdom has been an unreliable partner on border security for decades, even in the best of times. The coronavirus pandemic is about to expose the full measure—and terrible cost—of that corruption and incompetence.