The historic expansion of oil production in the U.S. has been a bright spot during an otherwise dismal recovery. But under an antiquated provision of federal law, it’s usually illegal to export crude oil from the U.S.

Ending the prohibition, as a bill in Congress would do, would increase economic activity and may reduce gasoline prices. The House Energy and Commerce Committee’s endorsement of the legislation late last week, and the full House’s expected passage, brings a renewed spirit of opportunity and prosperity. But the Obama administration has joined with environmentalists to oppose the bill.

Congress enacted the oil-export ban in 1973 because the Arab oil embargo threatened to make oil scarce in the U.S. and cause prices to skyrocket. Price controls and rationing were also enacted. These fiscal measures made a bad problem worse, as is typically the case with government intervention, contributing to long waiting lines at the pump and a severe recession from November 1973 to March 1975.

Though these other measures were eventually eliminated, the oil-export ban has stuck around. With the U.S. energy landscape looking drastically different, now is the time to end this ban and heal 42 years of damage done to America’s economy.

As seen in the chart below, in early 2011, owing to a combination of fracking and the “Arab Spring,” the two major globally recognized crude-oil prices — the price of Brent crude sourced from the North Sea, and that of West Texas Intermediate crude sourced from Cushing, Okla. — diverged, with the Brent price becoming much higher than WTI.

That spread represents an opportunity to sell American crude in countries that currently don’t have access to it. And as both the Congressional Budget Office and the Energy Information Administrationhave concluded, exporting crude oil would not drive up prices for American consumers. In fact, as the EIA reports, prices could actually fall, because U.S. oil companies would increase production, altering the global balance of supply and demand.

Even with an incentive to produce more, the U.S. will likely continue to import oil, because many domestic refineries are only able to handle the heavier Brent crude. With the increased WTI production from hydraulic fracturing in the U.S. and the lack of capacity to refine it, this has left a surplus of WTI oil, driving down its price and creating a situation where refineries must purchase Brent at a higher price. This contributes to higher gasoline prices and less economic activity than otherwise.

But this problem could be substantially resolved by ending the export ban, which drives a large part of the spread between the two prices. Basic economics shows that full competition on the global market will force the prices to converge to their long-term spread of about one dollar.

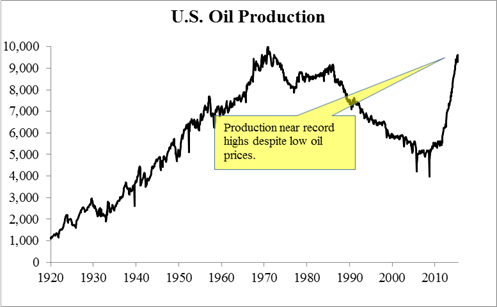

What about the plunge in oil prices since last summer and the subsequent drop in operating oil rigs? As seen below, this has so far not taken a toll on the colossal oil production increase, as the more efficient rigs remain online. The U.S. became the world’s largest producer of petroleum and related liquid fuels in 2013, whereby U.S. oil production has been three-fourths of increased global oil production and has reduced the nation’s oil imports by 60 percent since 2007.

Freeing oil producers to meet global demands will help improve energy-price stability, and also national security, by reducing our dependence on oil from unfriendly countries in the Middle East. Ending the export ban is one way America can reclaim President Reagan’s vision of a “shining city upon a hill” when things otherwise look dim.

Vance Ginn is an economist in the Center for Fiscal Policy at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a non-profit, free-market research institute based in Austin. He may be reached at [email protected].