Something happened last week that hasn’t happened in a long time—for the first time in a decade, Texas voters said “NO” to most school district bonds.

Here’s more from The Texan:

“Last week, a majority of proposed bonds on the November ballot failed for the first time since 2011, when only 17 of the 37 proposed bonds passed.

…..

“…the results show a clear shift from both previous years and even May of this year, when voters approved a whopping 93 of the 113 school bonds on the ballot.”

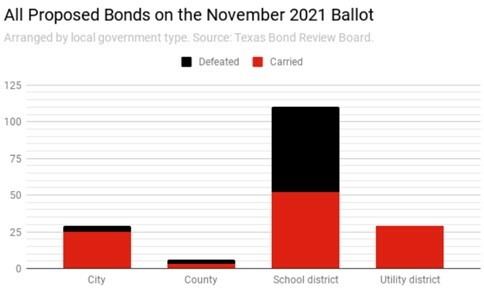

The November electorate clearly soured on ISD debt this cycle, especially when compared against May’s results. Curiously, though, the mood seemed limited to school district debt alone, which is evidenced by The Texan’s chart below.

All of this raises the question of why. It’s not entirely clear yet, but it likely has something to do with a mix of the following.

First, it could be that voters are taxed enough already. One recent comparison from the Tax Foundation suggests that Texans live under the sixth-most burdensome property tax system in the U.S. This point may have prompted many voters to think twice about shouldering any additional burdens that weren’t absolutely necessary.

Second, it could be that voters are better informed at the point of sale. Consider that in 2019 the Texas Legislature overhauled school finance with the passage of House Bill 3. One of its provisions now requires school districts to include a clarifying statement on every bond proposition, so that voters understand that a connection exists between new debt and new taxes. The statement reads: “THIS IS A PROPERTY TAX INCREASE.” This may have contributed to the pool of better-informed voters.

Third, it could be that voters are a bit more choosy. The legislature passed another bill in 2019, Senate Bill 30, that requires “to put forward separate ballot propositions to authorize bonds for the construction, improvement, or renovation of: a stadium; a natatorium; a recreational facility other than a gymnasium; a performing arts facility; and housing for teachers as determined by the district to be necessary to have a sufficient number of teachers for the district.” The new law effectively bans the old practice of offering up a massive single-item bond proposition and forcing voters to take it or leave it. It’s more of an a la carte approach that could have played a role.

Fourth, it could be that voters are alarmed by the amount of debt school districts have accumulated. In fiscal year 2020, local government debt totaled a staggering $375.7 billion. The political subdivision responsible for the greatest share: school districts, whose local debt service outstanding rose to $143.2 billion or about 40% of the total. Informed voters may well have hesitated to authorize any more borrowing given the current borrowing binge.

These factors as well as others, like timing, may have combined to sour the electorate on school districts’ big push this election cycle. What’s to be seen is whether it’s the start of a trend or a one-time affair.