FALFURRIAS—When Texas Gov. Greg Abbott sent a busload of illegal immigrants to New York City, the Big Apple’s Mayor Eric Adams said the action was “horrific.”

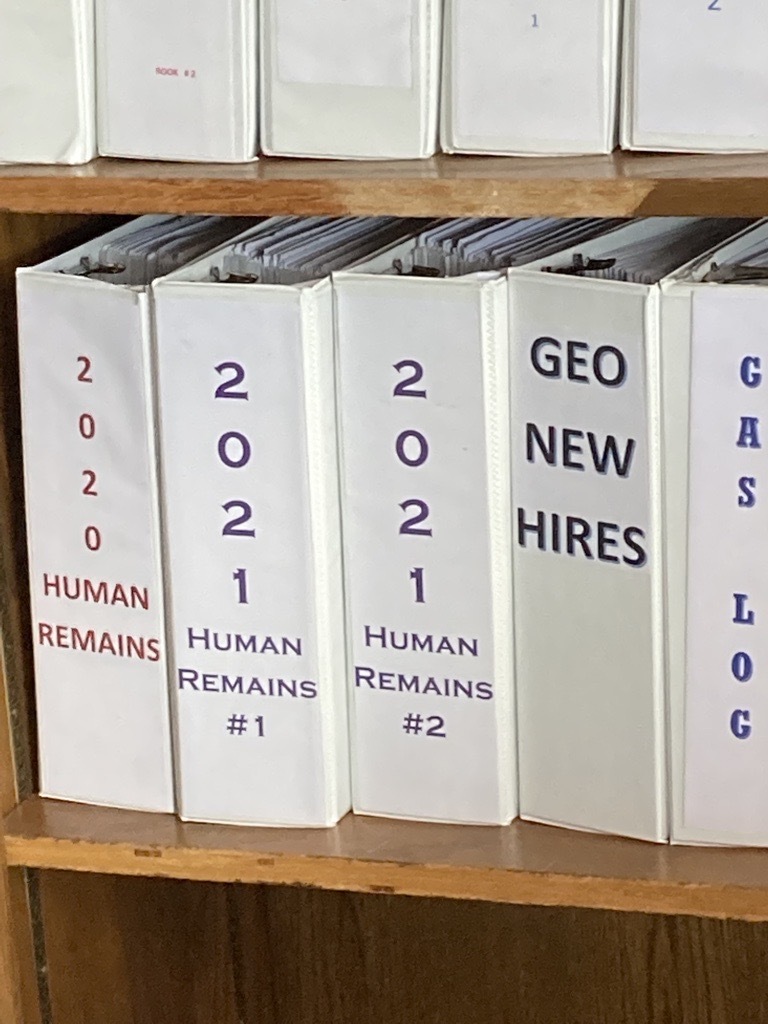

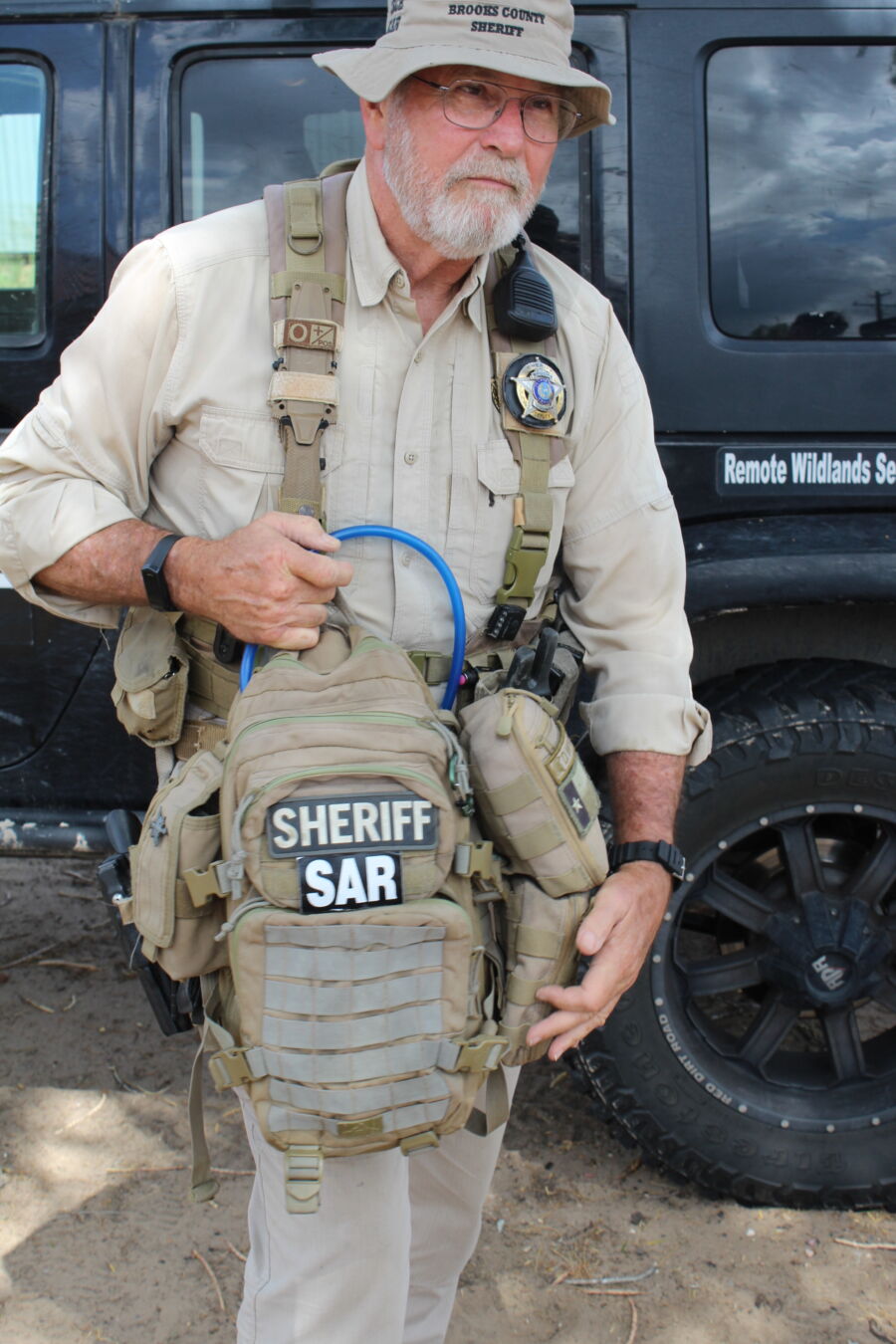

That’s a poor choice of words, according to Brooks County Deputy Don White. As the deputy tasked with search and rescue in the county with the highest number of migrant deaths in the nation, he knows what’s truly horrific—the cartel-driven violence, victimization and abandonment in the desert that has led to the discovery of more than 70 bodies in Brooks County so far this year. The mobile morgue provided by the state of Texas is nearly full.

White is a volunteer deputy who provides his own equipment, including the well-worn Jeep that allows him to navigate through the hundreds of square miles of scrubland in search of migrants in trouble.

He keeps medical equipment in that Jeep, including IV bags and first aid supplies. But the body bags he stores in the back are needed more often. While he does occasionally find migrants in time to save them, the heat, the long slog through sand and brush, as well as the human body’s own responses to dehydration too often have exacted their price.

Why is Brooks County, nearly 2,000 miles away from New York City and still miles away from the Texas/Mexico border, the epicenter for migrant deaths? It’s simple, really. U.S. 281 bisects the county and serves as a major artery for human trafficking going north. Border Patrol has a checkpoint on 281 on the south side of the county; the cartels that control the smuggling would rather not risk it. So they tell migrants to get out of the vehicle, and hike around the checkpoint—a hike of between 20 and 30 miles, depending on their path.

“At night, you can see the lights of Falfurrias in the distance,” White explains. “Sometimes they’ll tell the migrants, ‘See those lights? That’s Houston. Just go north, and you’ll find it.’ And, of course, they don’t.”

After their long journey north—through the entirety of Mexico itself, if they’re from Central America’s Northern Triangle—migrants are typically held for days or weeks in stash houses as the cartels extort even more money from their families. They’re poorly fed, the sanitation is inadequate, and they’re often weakened and sick by the time they leave the stash house.

Sometimes, a local “coyote” (slang for a human trafficker) will lead a group around that checkpoint. But if someone in the group can’t keep up, they’re abandoned. If that person has managed to hang on to a cell phone (the cartels usually take them away from migrants), they can call 9-1-1. More often, they’re left to try to find a way out of the mesquite-strewn desert by themselves. Sometimes they can hear a road; they might make toward it. They don’t always get very far.

“You can tell a lot by their footprints in the sand,” says White, a 59-year-old who retired from the microchip industry. “You can tell when they start to drag their feet, when they stumble. You can tell where they’ve fallen, and whether they are able to get back up. You can tell where they started crawling. And after that, you find them—their remains.”

White will occasionally get a call from a nonprofit agency that helps families who lost track of a relative attempting to make the journey. With little to go on, he’ll search the ranches and roadways of Brooks County. He estimates that he finds only a fraction of those who have lost their lives due to Biden’s border policies, which leave the Mexican criminal cartels in operational control of the U.S.-Mexico border.

White will occasionally get a call from a nonprofit agency that helps families who lost track of a relative attempting to make the journey. With little to go on, he’ll search the ranches and roadways of Brooks County. He estimates that he finds only a fraction of those who have lost their lives due to Biden’s border policies, which leave the Mexican criminal cartels in operational control of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Those non-profits also place water barrels throughout the county, in an effort to reduce the needless deaths. But those, too, are often dry in this arid heat. Even this symbol of hope is usually hollow.

Why does White face this horror, year after year? For the families.

“They deserve to know,” he says. “Everyone deserves to know what happened to their loved one. And we’ll make every effort to identify remains, and get them returned home. Where they belong.”