Part 4: Moral Problems With Student Loan Forgiveness

Student loan forgiveness also suffers from a variety of moral problems.

Forgiveness Pursued for the Explicit Purpose of Benefiting Certain Sexes or Races Is Wrong

Many advocates for student loan forgiveness are explicit that a main motivation for them is the argument that forgiveness would disproportionately benefit women or preferred races (Coalition letter to President Biden, 2021). This is an unjustified basis for advocating a public policy.

Public policies are not guaranteed to affect all sexes or races equally, and that is generally acceptable so long as the policy was not implemented with the explicit purpose of achieving such disparate impacts. For example, the number of women attending college outnumber men by over 30% (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.-b). Thus, any policy that benefits college students will have a disparate impact, benefiting women more than men. So long as the disparate impact is an unintended consequence, the policy should not be considered sexist. But if the government pursues a policy because of its disparate impact, then that is immoral because it is seeking to advantage or disadvantage certain groups of people based on sex.

The same argument holds for racial groups.

When the Roosevelt Institute argues that “student debt cancellation could be considered a form of racial reparations” (Eaton et al., 2021, p. 14–15) and that “one of the most important and well-documented benefits of student debt cancellation is … the potential to increase Black net worth” (p.5), they are advocating a policy for unjust reasons. If a policy is implemented for justifiable reasons and happens to increase Black net worth disproportionately, that is great. But if a public policy is pursued because it will disproportionately increase Black net worth (or any other race’s net worth), then that is an inappropriate reason to support the policy.

Progressives who support student loan forgiveness because of the racial implications are seeking to reestablish the worst parts of the world’s and America’s past—policies that explicitly favored one race over others—but with their preferred races as the beneficiaries. But previous policies in America that favored Whites were not unjust because they favored the wrong race, they were unjust because they favored any race over others.

In addition to being morally wrong, calls for universal loan forgiveness in the name of racial justice would actually exacerbate rather than alleviate differences in disposable income by race. Adam Looney estimates that “the average white household makes about $895 in annual student loan payments, slightly above the $839 in payments in the average Black household” which means that debt forgiveness would put “more cash into the pockets of white households each month” (Looney, 2022, p. 14).

Faith in Lending Would Be Undermined

Student loan forgiveness would undermine faith in public lending. The government offers grants—aid that does not need to be repaid—but does so to a much more narrowly targeted subpopulation of students, typically those from low-income backgrounds (e.g., the Pell grant) or those advancing the scientific frontier (e.g., National Science Foundation grants).

In contrast, because the presumption is that student loans will be repaid by the borrower, virtually anyone can get a student loan, and they can borrow vast sums that far exceed the grant aid provided to even the most economically disadvantaged students. Yet student loan forgiveness would transform all past lending into grants after the fact. This would undermine the public’s faith in lending. As Rick Hess notes,

The compact that undergirds any form of lending—but especially public lending—presumes that borrowers are taking responsibility for their choices. Typically, that means borrowing no more than is absolutely necessary, borrowing to meet needs rather than wants, and making good-faith efforts to repay in full. That kind of behavior fuels a virtuous cycle of civic trust.

Proposals for sweeping loan forgiveness shatter that compact in every possible way. (Hess, 2020, para. 10-11)

If student loan forgiveness is implemented, any future public lending program will operate under the justifiable suspicion that it is really a grant program in disguise.

Overpriced Colleges Would Be Rewarded

When a student borrows too much, some of the responsibility falls on the college for either charging too much or failing to provide an education that is remunerative enough to enable the student to repay their loans. Yet forgiveness would reward colleges that are overpriced. As Beth Akers writes, forgiveness would mean that taxpayers are financing a guaranteed bailout when students attend colleges that don’t deliver an education enabling them to earn enough to pay back the loans. This takes the pressure off the colleges to provide value while allowing them to benefit from rivers of cash. (Akers, 2019b, para. 5)

An illustrative example of this phenomenon is found in the Grad PLUS program, which allows graduate students to borrow without limit. As Charles Lane recounts,

Congress enacted Grad Plus thinking it would make graduate school more affordable, to the benefit of students and of the larger society. Instead, it enabled some universities to turn their master’s programs into cash cows and (some of) their graduates into modern-day debt peons… [Forgiving loans] would make taxpayers shoulder the entire cost of fixing this screw-up — from which many well-endowed universities profited. That hardly seems fair. (Lane, 2021, para. 11-12)

Student Loan Forgiveness Is Regressive

Virtually no one thinks that it is appropriate for the government to provide handouts to those with high incomes in the name of charity. Yet, to a disturbing extent, that is precisely what loan forgiveness would do. The reason for this result is that student loan debt is concentrated among high earners. Sandy Baum and Adam Looney (2020) document that “the highest-income 40 percent of households (those with incomes above $74,000) owe almost 60 percent of the outstanding education debt. … The lowest-income 40 percent of households hold just under 20 percent of the outstanding debt” (para. 3). This means that student loan forgiveness would disproportionately benefit upper-income households because they hold most of the outstanding student loan debt.

Consider the 7% of borrowers with more than $100,000 in student loans:

This small share of borrowers owes more than one-third of the outstanding balances. Doctors and lawyers and MBAs have lots of debt, but they also tend to have high incomes. … Forgiving all student debt would deliver a big windfall to a few people: those who can afford to pay. Virtually all of those with the largest debts have bachelor’s degrees, and most have advanced degrees. That is not a progressive policy. (Baum, 2021, para. 7)

In the most comprehensive analysis of who would benefit the most from student loan forgiveness, Sylvain Catherine and Constantine Yannelis (2020) find that “universal and capped forgiveness policies are highly regressive, with the vast majority of benefits accruing to high-income individuals” (p. 22). And the skew is substantial: “forgiveness would benefit the top [income] decile as much as the bottom three deciles combined” and “The average individual in the highest earnings decile would receive a little less than five times more forgiveness than the average individual in the bottom earnings decile” (pp. 1, 13).

Other analysts reach similar conclusions. Economist Justin Wolfers (2011) writes that “if we are going to give money away, why on earth would we give it to college grads? This is the one group who we know typically have high incomes, and who have enjoyed income growth over the past four decades” (para. 5). Anthony P. Carnevale and Emma Wenzinger (2021) conclude that “under a broad student loan cancellation program, more of the funds would go to higher-income college graduates who are already in a good financial situation to pay off their loans” (p. 9). And writing for Third Way, Shelbe Klebs (2021) argues that “universal debt cancellation plans offer a one-time, short-term fix—with a massive price tag that benefits upper-income Americans the most” (para. 3).

In the face of this overwhelming consensus that student loan forgiveness is regressive, some progressives have made two counterarguments.

Their first argument is that “the redistributive impacts of student debt cancellation should be measured across the full distribution of households, rather than solely among the beneficiary population” (Eaton et al., 2021, p. 8) because a policy could be regressive among beneficiaries but progressive across the whole population. They give the example of the Earned Income Tax Credit, which “may give a lesser credit to a worker who earns $14,000 than a worker who earns $19,000 per year, but the credits are all targeted at the lower end of the distribution, ultimately making it a progressive policy” (p. 8). For student loans, they argue that students from higher income households are less likely to take out student loans, so even though those who do borrow have higher balances, there are simply fewer of them compared to students from lower income households. This means that if student loans are forgiven, even though individual borrowers from an upper income family may benefit more individually, there are so few of them that most of the aggregate benefit accrues to those from lower income families.

Yet this argument is quite misleading. Regressive policies among beneficiaries that are progressive across the whole population are possible, as their Earned Income Tax Credit example demonstrates. Yet the regressive nature of the Earned Income Tax Credit among beneficiaries is there for a reason—to encourage recipients to work and increase their earnings. In other words, regressivity among beneficiaries is a tradeoff, an unintended consequence of the desire to maintain incentives for recipients to work. Yet there is no tradeoff for student loan forgiveness, where the regressive nature of the policy among beneficiaries serves no purpose other than to give a windfall to those with high incomes.

Moreover, the regressive nature of student loan forgiveness among beneficiaries could be easily eliminated by including income caps (often called means-testing), which would make the policy progressive among both beneficiaries and the overall population. While progressives do not object to means-testing for most other government programs, some are oddly hostile to an income cap for student loan forgiveness. The Roosevelt Institute argues that “income eligibility cutoffs and income-driven repayment are inefficient and counterproductive ways to achieve progressivity” (Eaton et al., 2021, p. 1). And 105 pro-forgiveness organizations argue that “an income-based means-testing regime, for instance, will direct relief to borrowers based only on a short-term snapshot of a borrower’s finances” (Coalition letter to President Biden, 2021, p. 5). We disagree. Including an income cap in any loan forgiveness policy would be an excellent way to ensure that it is progressive among recipients as well as across the population as a whole. Failing to include means-testing in loan forgiveness ensures that graduates with high income will receive massive windfalls.

The second argument some progressives make to distract from the regressivity of forgiveness is that “student debt cancellation represents a onetime wealth transfer to households’ balance sheets. As such, it is more appropriate to gauge its distributional impact across the distribution of household wealth … rather than across the annual household income distribution, as is common among those who claim student debt cancellation is regressive” (Eaton et al., 2021, p. 9).

There are two responses to this. First, a policy is traditionally considered regressive or progressive based on its impact across the income distribution, not the wealth distribution. It is perfectly fine to conduct a different analysis looking at the impact across the wealth distribution, but that does not allow one to characterize analyses that look at the impact of student loan forgiveness across the income distribution and find the policy to be regressive to be a “myth” driven by “misleading methodological foundations” (Eaton et al., 2021, p. 1) when it is standard practice to gauge regressivity by income.

Second, if you want to consider wealth rather than income, then you need to account for assets, not just liabilities since both influence wealth. For student loan forgiveness, that means accounting for the higher lifetime earning potential associated with having a college degree. Yet the Roosevelt Institute’s analysis does not do so, instead relying on a snapshot of wealth soon after graduation. This leads to a misleading picture of recent graduates’ financial condition. As Adam Looney explains, excluding the value of education from a calculation of net worth while including debt used to finance that education is like measuring a homeowner’s wealth by subtracting their mortgage but ignoring the value of the home itself. You’d find that homeowners were poorer than renters, and that people living in mansions were the poorest members of society.

That’s clearly wrong, yet advocates for debt forgiveness make the same mistake, arguing that recent college graduates with student debt have negative wealth and are thus worse off than otherwise similar Americans who have not gone to college. …

[S]tudent loan borrowers appear to be low wealth only because their valuable educational investments aren’t measured as an asset on their balance sheet. (Looney, 2022, p. 6)

Once the value of a college education is properly included as an asset, it turns out student loan forgiveness would primarily benefit those with higher wealth. This perverse result is driven by the fact that student debt is concentrated among higher-wealth households. The top 20 percent of households, ranked by wealth (including human capital), owe 31 percent of student debt. …The bottom 20 percent owe 8 percent. (Looney, 2022, p. 9)

The bottom line is that student “loan forgiveness is regressive whether measured by income, educational attainment, or wealth” (Looney, 2022, p. 2).

One of the main drivers of the regressivity of student loan forgiveness is graduate students. Graduate students—those with a master’s, professional, or doctoral degree—have the weakest case for loan forgiveness. They are the most highly educated (or at least the most credentialed) people in the country, meaning claims of being misled about the costs and benefits of their degree carry less weight. And they are also among the highest paid after leaving school, reducing the “need” for loan forgiveness. Yet graduate students would be among the largest beneficiaries of student loan forgiveness because they account for a disproportionate amount of student loan debt. Recently, “about 56 percent of student debt is owed by those with masters or professional degrees” (Looney, 2020, para. 6).

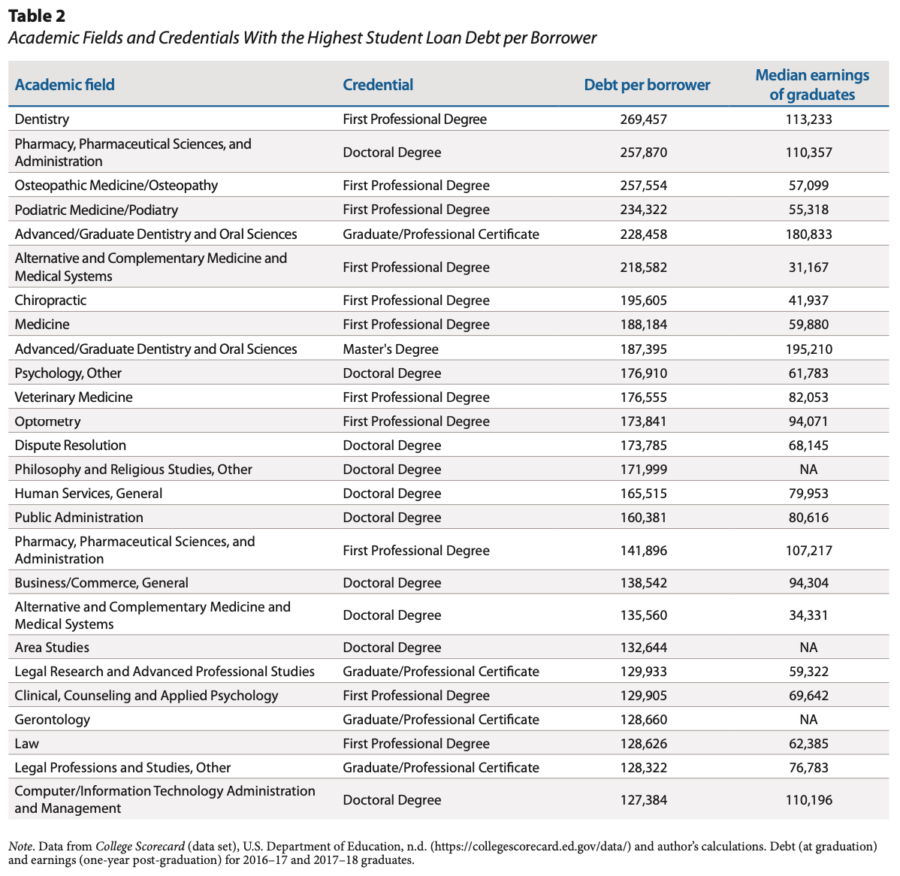

New data from the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.-d) provides a glimpse into how tilted toward graduate degrees loan forgiveness would be. Looking at all borrowers who graduated in 2016–17 and 2017–18, it is clear that the students receiving the most benefit from forgiveness are former graduate students. Table 2 shows how much debt would be forgiven for the 25 academic fields and credentials with the highest debt per borrower. All 25 of the fields and credentials with the most to gain from student loan forgiveness are graduate degrees. For example, the typical dentistry graduate with student loan debt would get a quarter of a million dollars gift from taxpayers, and lawyers with debt would get over $119,000. The next 25 fields are all graduate programs too, as are the 25 after that, and the 25 after that. In fact, the undergraduate field with the highest debt ranks 312 on the list, and those students would get just under $37,000 if their loans were forgiven.

Graduate students, given their years of education and relatively high salaries, have the weakest case to receive forgiveness. And yet they would be the biggest beneficiaries under these supposedly progressive proposals for loan forgiveness. Dropping graduate student debt from forgiveness proposals would dramatically reduce the price tag while simultaneously reducing the regressivity of forgiveness. Yet virtually no forgiveness proponents support eliminating graduate student debt from forgiveness proposals.