This commentary originally appeared in Forbes on February 26, 2016.

Think the federal government is the only one with a debt problem? Think again.

According to the Texas Bond Review Board (BRB), the state agency charged with overseeing debt issuances, Texas’ total local debt (including principal and interest) exceeded $338 billion in 2015. This means that every man, woman and child in the state owes about $12,250 for his or her share of all the debt incurred by city, county, school and special purpose governments. And the tab for Texas taxpayers is growing fast.

Just five fiscal years ago, in 2010, Texas’ local debt totaled $309 billion. Since then, however, local governments have gone on a borrowing binge, adding $30 billion in new debt, which works out to be almost $13,000 borrowed and spent for each new Texan.

Putting Texas’ problems into perspective

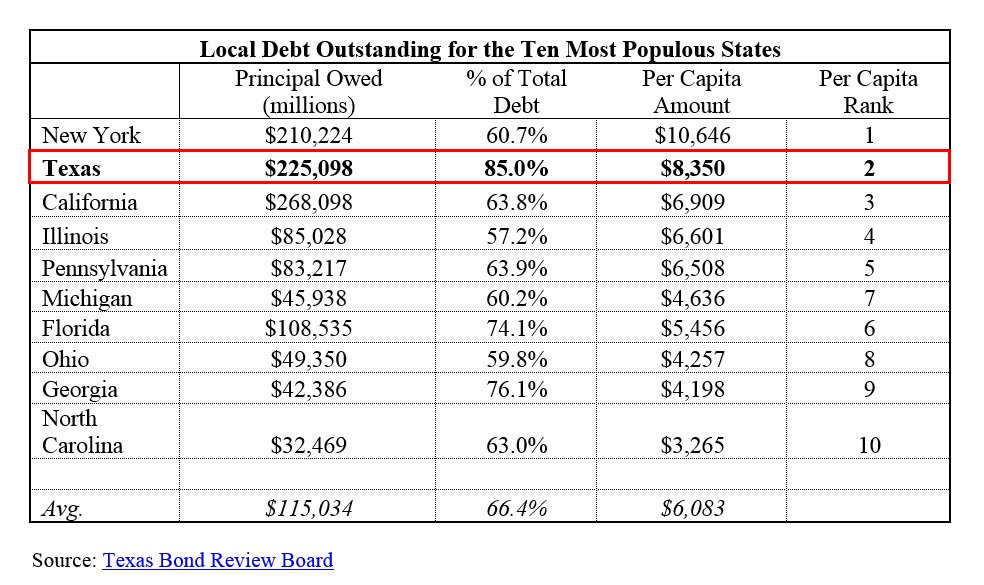

To put Texas’ local debt problems into perspective nationally, consider a new report from the BRB: Among the top ten most populous states in the nation, the principal amount owed by Texas is $225 billion and is the 2nd largest total next to only California who is $268 billion in the hole. Meanwhile, Texas’ local debt per capita of $8,350 ranks as the 2nd highest total, behind only New York’s $10,646 per capita. Both the aggregate amount owed and the debt per capita are well in excess of the nationwide averages.

As Texas’ appetite for debt has grown, so too has the tax burden necessary to sustain it. In an environment of elevated debt and accompanying debt service payments, Texas’ property tax—levied exclusively at the local level and their main source of tax revenue—is one of the nation’s worst. According to one measure from the Tax Foundation, the state has the nation’s sixth-highest effective property tax rate.

Texas is clearly facing an uphill battle when it comes to debt, but there’s an easy path to right the ship and stave off future fiscal crises. And it starts with education.

Educate voters

Right now, Texas voters aren’t provided with enough information at the ballot box to make an informed decision about government spending. Ballot propositions, sometimes worth as much as $1 billion or more, include only two bits of information at the voting booth:

1. A general description of the project that is usually written in legalese and worded broadly enough to mean almost anything; and

2. The principal amount to be borrowed that understates the bond’s total cost since it excludes interest.

With so little information provided to voters, it’s little wonder that many bad debt decisions have piled up. Fortunately, the solution to this problem is straightforward—arm voters with basic financial facts at the ballot box.

Although policymakers shouldn’t overload voters with information, there should be enough detail that a layperson can understand, such as:

- How their tax bills will be affected

- How much the bond will cost in full (principal and interest)

-

How fiscally responsible the local government asking for more debt has been up to this point, i.e. local debt service outstanding per capita

Look to other states for successful models

Voter education is, of course, only one piece of the puzzle. Policymakers also need to consider stricter controls on nonvoter approved debt instruments, like certificates of obligation. These types of debt devices were originally created to deal with emergency situations—think natural disaster recovery—but have increasingly been used by city councils to purchase things they don’t want to put in front of voters.

Another effective way to ease the swell of debt is using zero-based budgeting, which is a public finance technique to build the budget from the ground-up. It often requires more time and effort up-front from policymakers, but the budget is better and leaner, and the efficiencies found can be set aside to cut taxes so the productive private sector can flourish or help pay for future capital improvements.

Finally, it’d behoove Texas policymakers to look around the nation for models of successful local debt limitations. A debt ceiling of some sort, with flexibility for emergencies, may be needed. Much like parental involvement is needed when a young 20-something gets in over their head with their first credit card.

Texas’ local governments are in a deep, dark debt hole–and it is obvious that we must get back to the core conservative principles and values that built this country and made it great. Certainly not an easy feat, but not an impossible one either, especially with the right policy prescriptions in place.

Dr. Ginn is an economist at the TPPF. Mr. Quintero is director of the Center for Local Governance.?