Unlike the federal government, Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution prohibits states from issuing their own money. State power to tax and borrow is thus limited only by economics and commonsense.

Some states rely heavily on volatile revenue sources, such as personal income taxes with high marginal rates or excise taxes on oil and gas. For these states especially, saving money for a rainy day is vital to avoid sudden budgetary pain.

For example, in California, the top 1% of earners pay more than half of the state income taxes, which make up about 44% of the state’s general fund revenue. With the nation’s highest marginal income tax rate—13.3% on income in excess of $1 million—any downturn in income from California’s top earners will be quickly felt in the state treasury.

Unfortunately, California lawmakers view their steep progressive income tax as more than a way to fund government, they see it as a way to redistribute wealth, in spite of evidence to the contrary with the nation’s highest Supplemental Poverty rate.

And just as newly-elected California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced plans to spend $144.2 billion (a $5.5 billion increase from Gov. Jerry Brown’s last budget), the State Controller announced that revenue fell $4.8 billion short of expectations in December.

In New York, where the legislature raised $2 billion in new corporate taxes last year and the top personal income tax rate is 8.82%, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that income tax revenues dropped by $2.3 billion , declaring the shortfall to be “…as serious as a heart attack. This is worse than we had anticipated,” adding that “This is the most serious revenue shock the state has faced in many years.”

Cuomo blamed the revenue shortfall on federal tax reform signed into law by President Trump in December 2017 that, while cutting taxes, limited the federal deduction for state and local taxes to $10,000 per filing household—curtailing what amounted to a federal subsidy for high state and local taxes.

Cuomo warned that “This reduction must be addressed in this year’s budget” as he implored the legislature to cut spending and boost the rainy day fund.

Nationally, as of fiscal 2019, states had accumulated about $87 billion in fund balances, including about $63 billion in formal rainy day funds—about 10% of state expenditures.

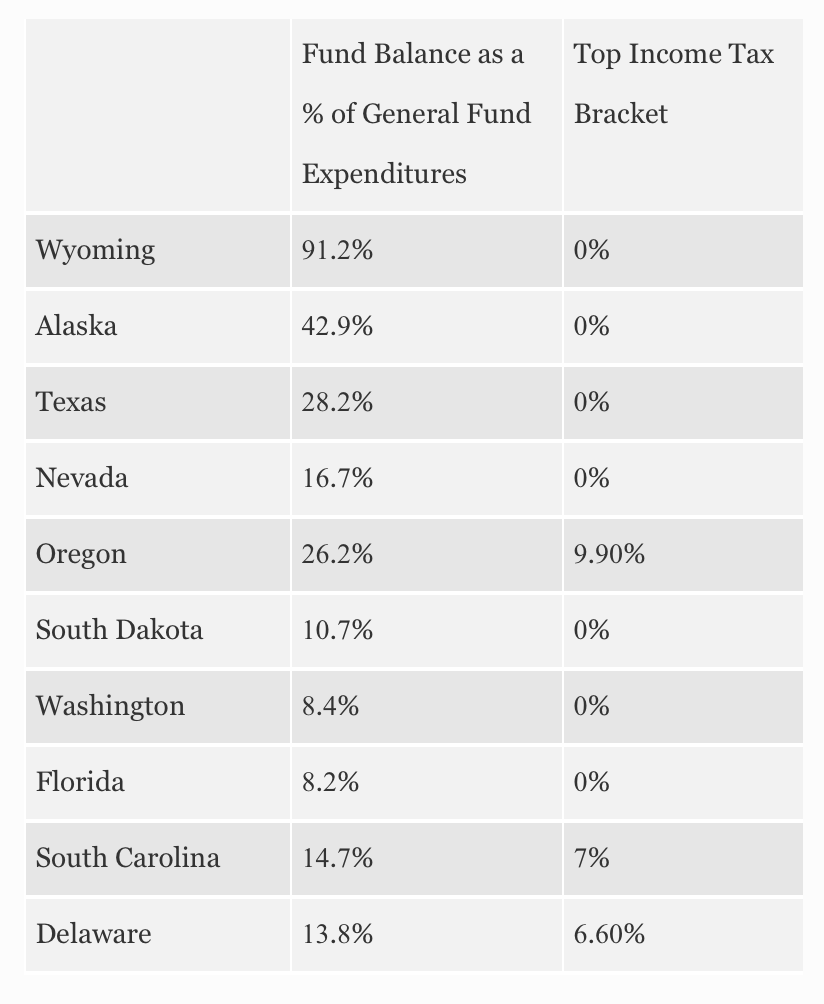

The states with the largest fund balances as a percentage of general fund expenditures are Wyoming (91.2%); Alaska (42.9%); New Mexico (33.9%); and Texas (28.2%). All of these states generate considerable tax revenue from energy extraction, a volatile revenue source.

The states with the weakest fund balances are Pennsylvania (0.1%); Illinois (0.4%); Kentucky (1.1%); and New Jersey (2.1%).

Comparing current state fund balances, income tax rates, and a state’s overall tax burden, a basic gauge of state fiscal health can be determined, providing general guidance as to the likelihood of a state coming under budgetary pressure to curtail spending or raise taxes.

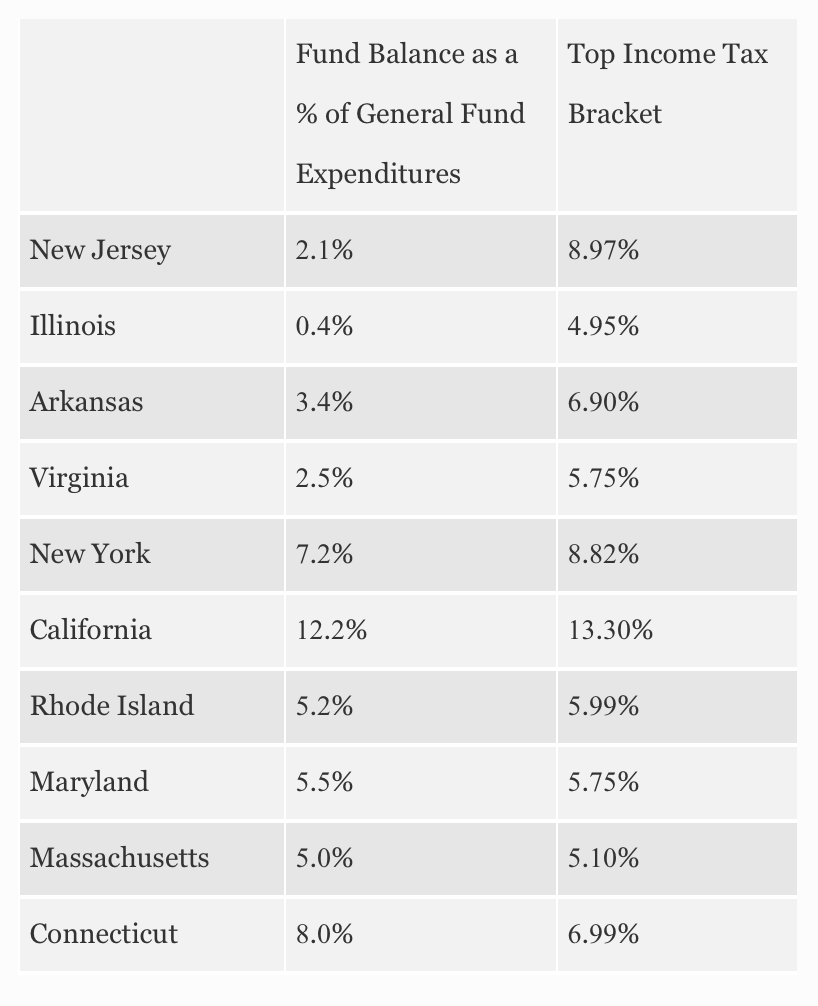

The 10 states with the highest short term fiscal risk, starting with the state in the greatest fiscal danger, New Jersey, are:

Additionally, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Minnesota and Maine may face budgetary challenges this year.

On the positive side of the ledger are states that have saved for a rainy day and, through a combination of low taxes or reliance on less volatile revenue sources, are in good shape to finish 2019 without extraordinary fiscal pressures. Of note is Oregon, a state with no sales tax and relatively high overall taxes and income taxes, but, possessing the fifth-highest fund balance as a share of general fund expenditures. Thus, while it’s likely Oregon will see a decline in income tax revenue, it is well-positioned to weather the drop in the short term.

Lastly, it’s important to note that this analysis doesn’t account for unfunded government employee pension or government retiree health insurance obligations. Because these obligations are amortized over decades and often represent a large share of the state budget, deferring payment or paying down the obligations can have a major effect on current-year budgeting. States with significant unfunded pension liabilities include Illinois, Connecticut, Kentucky, New Jersey, and Maryland.

Lawmakers in high-tax states facing budget shortfalls this year will be under tremendous pressure to raise taxes on the rich. But even Gov. Cuomo acknowledged the limits of such a fiscal strategy when he observed, “Tax the rich, tax the rich, tax the rich. The rich leave, and now what do you do?”

Conversely, lawmakers in low-tax states such as Texas and Florida must resist the temptation to increase spending in excess of taxpayers’ ability to support government, understanding that their past restraint on taxes and prudence on spending is what led to their strong balance sheets and vibrant economies.